| بازگشت به صفحه اول |

|

The 300 Movie: Separating Fact from Fiction

Dr. Kaveh Farrokh

Grossing over 70 million dollars in its first week of release, the movie “300” is set to crash into the list of highest grossing Hollywood blockbusters. Its strong opening is a clear indicator of its success with the North American and by implication, European audiences. Although this picture is based on a graphic novel by Frank Miller and directed by Zack Snyder (“Dawn of the Dead”), it is already being portrayed as a “historical” movie, and will be perceived as such by many (less discerning) viewers. More significant however, are the conclusions that are being derived from this picture.

The producers of the movie (as well as the actors) are honest in stating that they did not consult primary historical sources. The writer of the comic book appears to have relied on the writings of Greek historian Herodotus, whose works, though valuable, inevitably contain an element of bias, as do any historical works from any culture.

My article will not discuss the cinematography (a job best left to the film critics), nor is it a criticism of the cast and crew. There has been no agenda on the part of the original novelist, movie director, cast and crew to promote an anti-Iranian agenda. The movie however (no matter how sincerely it was intended as entertainment), is nevertheless purveying messages; messages most certainly unintended by Miller or the film producers.

The following commentary is specifically directed against the very human biases and distortions that currently pervade against ancient Iran and Iranians; the very same views that “300” has (inadvertently) stimulated.

Though perhaps trivial, I feel my background gives me a unique perspective. Born of Iranian parents in Greece, I am a student of both ancient Greece and its “East Roman” successor, Byzantium, alongside my main research interest, ancient Iran. My Greek friends often cite me as a blend of ancient Iran (or what the west terms as “Persia”) and “Hellas” (Greece). It is often overlooked that an Iranian can admire ancient Greece just as a Greek can do likewise with Persia. A Greek friend stated this to me in an e-mail on Monday, March 12, 2007:

“I watched the movie 300…and I was totally disappointed…The movie demonized the Persians, everything that was depicted in the movie about the Persians was untrue. The movie demonized also the Greeks and through some words of Leonidas Greek philosophers and Athenian civilization were downrated…I wonder why I should watch demons and Spartans with a false image…there was no showing of glorious brave and smart people from both sides. I have learned that what Spartans did in Thermopyles was magnificent, that they did not match any enemy but what they did there was really magnificent because it was achieved against a very brave, worthy and glorious enemy. …very few understand it.”

In the course of their historical intercourse, Greece and Persia have created breathtaking works in domains such as the arts, architecture, sciences, music and of course, democracy and human rights. It is interesting that many modern Greeks acknowledge and appreciate ancient Iran as a civilization as worthy as their own, yet the same is not necessarily true in northwest Europe and North America.

This review will focus on eight items for discussion:

(1) The Notion of Democracy and Human Rights

(2) What really led to War

(3) The Military Conflict: Separating Fact from Fiction

(4) The Error of Xerxes: The Burning of Athens

(5) The “West” battling against the “Mysticism” of “the East”

(6) The Portrayal of Iranians and Greeks

(7) A Note on the Iranian Women in Antiquity

(8) “Good” versus “Evil”

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

(1) The Notion of Democracy and Human Rights.

What struck me about the movie was its portrayal of the Greco-Persian Wars in binary terms: the democratic, good, rational “Us” versus the tyrannical, evil and irrational, “other” of the ever-nebulous (if not exotic) “Persia”. Central to this dichotomy is the following message:

“300 men stood between victory and the collapse of Western civilisation.… If the barbarian hordes…overran these defenders, Greek democracy and civilisation would fall prey to alien forces whose cruelty was a byword.”

[Christopher Hudson, “The Greatest Warriors Ever”, Daily Mail, London, England, March 9, 2007]

Note the key words “collapse of Western civilization”, “barbarian hordes”, “democracy and civilisation” and “alien forces whose cruelty was a byword”. These key words are reminiscent of political sloganeering, targeting the “other” with slanderous propaganda. These simplistic (and patronizing) statements are a clear indication that the general media and much of the audience is seeing “300” as much more than just a movie of a “graphic novel”. This has been astutely observed by Tomas Engle, a student at a West Virginia College, who has noted with some concern that many people are viewing the movie to “inform themselves on history." [http://www.lewrockwell.com/orig8/engle1.html].

The citations from popular media outlets (such as The Daily Mail) are yet another vivid demonstration of the gross prevailing ignorance as to the actual origins of the notions of human rights, democracy and freedom, as well as the complex factors that led to the Greco-Persian wars.

The origins of democracy and human rights are not as simple as we are led to believe. As we will see below, these notions share both Greek and Iranian origins.

Meanwhile, the Greeks (the Athenians and their Ionian kin in particular), created the notion of “Demos” (the people) and “Kratus” (government). This government by the people is what excites the imagination of the contemporary “western world”. However, few acknowledge the role of “the East” in helping place modern democracy as we know it today, within the context of racial, religious and cultural equality, or (more succinctly), human rights.

The founder of the Achaemenid Empire, Cyrus the Great, was the world’s first world emperor to openly declare and guarantee the sanctity of human rights and individual freedom.

Cyrus the Great as reconstructed by Tim Newark, 2000, p.21

(Ancient Armies, Concord Publications, painter Angus McBride)

Cyrus was a follower of the teachings of Zoroaster (Zarathustra), the founder of one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions.

Portrait of Zarathustra as depicted in a Mithraic Temple in Dura Europus (in modern Syria) in the 3rd Century AD.

Zoroaster taught that good and evil resides in all members of humanity, regardless of racial origin, ethnic membership or religious affiliation. Each person is given the choice between good and evil – it is up to us to choose between them. It is that goodness, and a firm belief in its divinity, that is the key to human liberty, according to Zoroaster. As a consequence, every individual is entitled to liberty of thought, action and speech. This is enshrined in Zoroaster’s guidelines: Good Thoughts (Pendar Nik), Good Deeds (Kerdar Nik) and Good Speech (Goftar Nik).

As a result, freedom of thought, action and speech are laden with the awesome responsibility of wielding these for the good of all mankind. Zoroaster taught that there is no such thing as a “bad race” or “bad religion”. The only divide is that between good and bad people, both within one’s own community and those outside of one’s community. Zoroastrians often referred to ancient Iran as “the land of the Free/Freedom” (Zamin Azadegan).

Zoroaster preached the concept of an all-powerful single god known as Ahura-Mazda (the Supreme Angel), who stood for all that is good. However, the acceptance of Ahura-Mazda was a personal choice. There were to be no forced conversions and the gods of all nationalities were fully respected: Cyrus prostrated himself in front of the statue of Babylonian god Marduk after his conquest of Babylon. As noted by Graf, Hirsch, Gleason, & Krefter “Belief in a heavenly afterlife for good people and torment for evildoers may have been partly responsible for the moral treatment that Achaemenid Kings accorded subject nations…”[i]

The Greek warrior-historian Xenophon, spoke highly of Cyrus in his Cyropaedia. Cyrus is described as being void of deceit, arrogance, guile or selfishness. Cyrus is the first “one world hero” in history, namely the ruler who sought to unite all the peoples into one empire while according full respect to all languages, creeds and religious practices. Alexander the Great, who greatly admired Cyrus, adopted his mantle of the “world hero” after his conquests of Persia in 333-323 BC.

Cyrus’ system of government has been forever immortalized by the Cyrus Cylinder. This is a clay cylinder of a decree that was issued by Cyrus the Great in 538 BC shortly after his conquest of Babylon.

The Cyrus Cylinder. This is the first human rights charter in history. A facsimile of the Cyrus Cylinder is present at the United Nations building in New York City

There three main premises in the decrees of the Cyrus Cylinder were:

(1) the institution of racial, linguistic and religious equality

(2) all exiled peoples were to be allowed to return home

(3) all destroyed temples were to be restored.

When Cyrus defeated King Nabonidus of Babylon, he officially declared the freedom of the Jews from their Babylonian captivity. This was the first time in history that a world power had guaranteed the survival of the Jewish people, religion, customs and culture. Cyrus allowed the Jews to rebuild their Temple and provided them with funds to do so. The empire continued that support as indicated by a decree by Darius the Great in 519-518 BC by allowing the Jews to complete the reconstruction of the Jerusalem Temple (Ezra, 4:1). Cyrus’ magnanimity is reflected in the Old Testament where he is cited as Yahweh’s anointed (See Book of Ezra 1). Koresh (Hebrew for Cyrus), was hailed as a Messiah by the Jews. Isaiah cites Cyrus as “He is my Shepherd, and he shall fulfill all my purpose” (Isaiah, 44.28; 45.1). The Biblical characters Ezra, Daniel, Esther and Mordecai played historically important roles in the Persian court. The tomb of Esther and Mordechai still stands to this day in Hamadan, the site of the ancient city of Ecbatana, a city that has hosted Jews for over 2500 years. The Persian king Xerxes himself was married to a Jewish queen named Esther.

A more humane 1962 Hollywood picture of ancient Iran: Xerxes (played by Richard Egan) and his Jewish queen Esther (played by Joan Collins)

Tomb of Esther and Mordechai in Hamedan, Iran.

Professor Victor Davis Hanson (Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Professor emeritus at California University) summarizes the issue of “Freedom versus Tyranny” very succinctly:

“If critics think that 300 reduces and simplifies the meaning of Thermopylae into freedom versus tyranny, they should reread carefully ancient accounts and then blame Herodotus, Plutarch, and Diodorus — who long ago boasted that Greek freedom was on trial against Persian autocracy…in almost all wars, one side is defending its freedom. The Greeks were not the first human beings to defend their freedom…monarchy is not something Eastern…when these 'freedom-defender' Greeks were united under Alexander, they did the same thing…they invaded Persia, Egypt and India and created their own empire…so did their Roman successors…”

[For full text see: http://www.victorhanson.com/articles/hanson101106.html]

(2) What Really led to War: The Untold Story

As noted above, Western popular opinion and academic historiography portrays the Greco-Persian wars as being an epic contest between liberty, as represented by Greece, and “Persian Tyranny”. Professor Richard Nelson Frye, however cautions us that such historical narratives are “…an example of imposing modern concepts on the past…distorting our understanding…” [Richard Nelson Frye, 1984, p.93

Yes, indeed it is true that the Ionian revolt on the west Anatolian coast and the support of the Athenians for their Hellenic ethnic kin against the Persian Empire was a major factor that led Darius the Great (549-486 BC), the father of Xerxes, to invade Greece in 490 BC. But this is only a part of the story. Very few western historians have discussed the role of economic rivalry as a factor in the Greco-Persian wars.

By this time, the Greeks had established a powerful maritime economic empire in the Mediterranean Sea. The Greeks established colonies in southern Italy as well as contemporary southern France; an example of this legacy is seen in the name of the city of “Nice” (pronounced /nees/) in southern, France – “Nice” is derived from the Greek Nicea (modern Nice). Greek trading posts had also been established in the Caucasus, in the Modern Republic of Georgia.

The Achaemenid Empire became a marine empire as soon as it reached the Aegean Sea. Darius the Great built the world’s first formal “Imperial Navy”, many of its ships manned by Phoenician, Egyptian and (Hellenic) Ionians. More importantly, the Persian Empire began to “muscle in” on the economic sphere of the Greeks in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea (see Cook, The Greeks in Ionia and the East, 1962, 98-120; 132-133; Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War, 2007, Chapter 4). Italian researchers such as Nik Spatari have confirmed that Darius had sent naval scouts as far as Southern Italy to gain information on possible trade contacts with the western Mediterranean (Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapter 4).

Reconstruction of Achaemenid ships in 1971.

Persia’s growing economic strength in the Mediterranean was certainly of great concern to the Greeks and their prosperity. The Greco-Persian wars were as much about economics, as they were about systems of government. For further references consult the bibliography.

(3) The Military Conflict: Separating Fact from Fiction

There are very few historians who doubt the tenacity and military skill of the Greek defenders who faced the invading army of Xerxes. The 300 movie displayed the equipment of the Spartans relatively well, considering that the producers were intent on reproducing the images of a comic book, leaving little room for consultation with modern scholarship. If the portrayal of the Greek side was adequate, that of “the Persians” was pure fantasy. This being said, there are already a large number of viewers who have taken these images in a very “literal” and historical context – the human mind is indeed a very impressionable organ.

The discussion here is a very quick and overall analysis of the actual military factors that were in place during Xerxes’ invasion of Greece in 480 BC – however we will digress into the post-Alexandrian eras, notably the evolution of the Persian knights during the Parthian (238 BC- 224 AD) and Sassanian (224-651 AD) eras. I will closely scrutinize the veracity of whether Xerxes actually wielded 1,700,000 troops during his invasion of Greece. By no means is this discussion adequate, however it is hoped that the reader’s curiosity will be sufficiently evoked as to encourage further research and readings.

Weapons.

Greek spears and swords were longer than their Achaemenid counterparts. This meant that in hand to hand combat, the Spartans held the advantage and were able to “outrange” their opponents with their swords and spears, which were primarily used for thrusting (see Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapters 4-5). The swords of “the Persians” in the movie are of no historical relevance – many of the Iranian swords of that era were short and dagger-like. These were known as the “Akenakes”.

Scythian (left) and Mede (right)

Saka Tigrakhauda (Tall-capped Scythian to the left) and a Mede (round cap to the right) appearing before the Achaemenid kings at the Imperial palace of Persepolis. Note the short size of the Akenakes daggers, which proved inadequate in hand to hand combat against Greek warriors.

For a thorough examination of the Akenakes daggers, as well as all Iranian military gear from the Bronze Age to the 19th century, consult Manoucher Moshtagh Khorasani’s comprehensive book on the subject:

Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to end of the Qajar Period

http://www.arms-and-armor-from-iran.de/

Armor.

Greek troops were far better armored than their opponents, although it is not clear if all the Spartans wore heavy armor at Thermopylae. Greek helmets, body armor and greaves provided excellent protection against blade weapons in hand to hand combat, whereas the vast majority of the Achaemenids lacked significant armor protection. Scale armor was available, but not to the majority of troops. When engaged in hand to hand combat, Achaemenid troops were exposed to deadly spear thrusts as well as hacking/thrusts against their faces, limbs and torso (see Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapters 4-5). The movie portrayal of Achaemenid armor, was pure fiction and has no resemblance to that issued among Achaemenid troops.

The Martial Arts Tradition of Greece.

The 300 movie did capture the camaraderie, zeal and “esprit de corps” of the Spartans very well, and represented the contemporary military culture of ancient Sparta in a fairly realistic manner.

Greece (as a whole) was the heir to an excellent martial arts tradition. According to legend, the newborn child in Sparta would be washed by his mother in wine to ensure that the child was strong and fit (the weaker baby would reputedly die from the bathing). The father would then bring the baby to advisors who would ultimately decide if the newborn child was fit to be raised as a Spartan. If the baby “failed” the test, he would cast off a cliff or gulley at Mount Taygetos, known as the “Kaiada”.

As shown in the movie, the boys of Sparta began training from the age of 7. Formal military service would begin at the age of twenty. Examination of Greek vases clearly shows Greek warriors engaged in very “modern” training methods: kicking, boxing, wrestling, Pankration, using “speedbags”, etc.

Greek warriors engaged in martial arts “kick boxing” training – note “coach” to the right.

Training and drills were at least as brutal as combat situations. Sparta was very much a warrior society; it was the Athenians and their ethnic cousins in Ionia (modern western Turkey), then under Persian rule, who were at the forefront of the Hellenic Democratic tradition.

The Greek Phalanx System.

The Greeks in general had developed the phalanx system, where soldiers fought as one unit in a single formation. Central to this system was the use of overlapping shields which formed an impenetrable barrier against javelins, spears and arrows. The Macedonians of northern Greece, perfected the phalanx and adopted the 12 foot long pike or “sarissa” used with devastating effect by Alexander the Great during his invasion of Persia.

The Chiqi vase which shows a Greek Phalanx

(Source: http://www.livius.org/)

The Greeks often engaged in close quarter combat and had been doing so for centuries before the Achaemenid invasions. Suffice it to say that when it came to hand to hand combat, the Spartans held the advantage. Thanks to their training, the Spartans were os disciplined that they were able to collectively maneuver the phalanx at a single command. With their shields locked together, the phalanx was able to march and put forward all of their spears simultaneously. There was no breaking of formation in acts of battlefield individualism – all warriors were expected to adhere strictly and steadfastly to the phalanx. The spears protruded in deadly fashion towards the onrushing enemy, with deadly results. The Greeks testify to the bravery of the lightly armored Iranians who tried to break the spears of the Spartans with their bare hands in an endeavor to get close to the warriors within the phalanx.

The Evolution of cavalry.

The portrayal of “Persian cavalry” was totally wrong in the movie with respect to weapons, equestrian gear and uniforms. Superficially, these resembled more the Arab horsemen seen during the Arabo-Islamic conquests over a thousand years after the Battle of Thermopylae and bore little resemblance to either the Iranian cavalry of the Achaemenid era (559-333 BC), or the armored knights of the later Parthian and Sassanian eras of Persia (238 BC - 651 AD). Below is a reconstruction of Iranian heavy cavalry of the Achaemenid period.

Mede Cavalryman of the later Achaemenid era

Despite their formidable armor, Achaemenid cavalry had yet to solve the problem of rider stability, especially against well-trained, heavily armored, lance/spear wielding infantry fighting in phalanxes (see Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapters 4-5). This is mainly because the Iranians had not yet invented saddle technology advanced enough to keep the rider stable enough as he fought on horseback. As a result, Iranian cavalry during the Achaemenid period was vulnerable to unseating by Greek heavy infantry, a fact that was duly observed by Xenophon in the early 400s BC.

Nevertheless, Iranian cavalry continued to evolve, even after the Alexandrian conquests of the Persian Empire. It was the cavalry which had posed the greatest challenge to the Greeks during their conquests of Persia, and the Greeks were duly impressed by them. Xenophon warned about the dangers of the Iranian cavalry, a prophecy which was to prove true with the rise of the Parthians and the Sassanians. It was these new Persian knights who finally defeated the Seleucid successors of Alexander and who scored dramatic victories against Marcus Lucinius Crassus at Carrhae (53 BC), and against Roman Emperors Severus Alexander (Ctesiphon in 233 AD), Gordian III (Mesiche in 244 AD), Phillip the Arab (Barbalissos in 253 AD), Valerian (Carrhae-Edessa in 260 AD), and Julian (inside Persia in 363 AD). By the 5th century AD, the Turks had arrived from the North of China into Central Asia and Europe, and were influencing the Iranians and the Romans: the Turks were probably the first to invent stirrups.

Very few are aware of the positive references to the military skill of the later Persian knights. One example is Libianus who, referring to the Sassanian knights, notes that Roman troops “prefer to suffer any fate rather than look a Persian in the face” [Libianus, XVIII , pp.205-211; Consult also Farrokh, Sassanian Elite cavalry, 2005, p.5]

The Pushtighban Heavy Knights of the Royal Guard (left) and Jyanavspar-Peshmerga (right) engaged against Roman troops during the failed invasion of Emperor Julian in 363 AD (Farrokh, Sassanian Elite Cavalry, 2005, Plate D; Paintings by Angus McBride).

Much of the armor of these knights appears very “European”; the warriors wear mail, plate armor, riveted Spangenhelm helmets, broadswords, maces and battle-axes. Yet these warriors predate their European counterparts by centuries (see Farrokh, Sassanian Elite Cavalry, 2005).

Though the Spartans (and indeed the Greeks as a whole) are rightfully remembered as magnificent warriors whose exploits and heroism resonate across time, Persia too gave birth to magnificent military tradition: the Partho-Sassanian elite cavalry, known as the “Savaran.” Is it not interesting that nobody has even heard of the Savaran? As noted by Greek-Canadian historian, George Tsonis: “Unfortunately we probably will never see movies of Roman defeats in “the east” at the hands of Persian knights…such movies would most probably bomb at the box office.”

This bias is not confined to the entertainment media. The academic community (mainly in northwest European and English-speaking world) has until recently continued to champion ancient Greece and diminish, sideline and even ignore the Savaran. This bias can be seen in the comments of world renowned military historian, Professor John Keegan, who in reference to the Persian influence on western European cavalry states in no uncertain terms that: “True, the Persians…had fielded squadrons of armored horsemen and even armored horses at an earlier date [than the western Europeans]…to ascribe the origin of heavy cavalry warfare to them is risky.” [Richard Keegan, A History of Warfare, 1993, p.286]

Professor John Keegan

Keegan’s interpretation is essentially rejected by a large number of historians such as Herrmann, Michalak, Inostrancev, Nickel and Newark (see discussion by Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapters 9-22, 24). Professor Keegan represents a more selective interpretation of the history of cavalry, one that has sought to diminish the role of Persia in particular. As noted by another Greek colleague, “Stamatis”:

“…there is no need for academics to denigrate Persia just to preserve the glory of ancient Greece. Both Greece and Persia are glorious in their contributions to world civilization. Comments such as these are more a product of academic dogma rather than true scholarship. One sees such scholarship in ancient Greece, Persia, Egypt, China and the golden age of Islamic learning where non-Arabs such as the Iranians made mighty contributions …

The Immortal Units.

Perhaps most interesting was the portrayal of the Immortal units of the Achaemenids. Superficially, they resembled Hollywood-style “ninjas”, dressed in black. Black and dark clothing were not featured among any of the standard Achaemenid troops. The superficially “Oriental” looking iron face masks were never used by the elite troops, and as noted above, Iranian units (in general) were more lightly armed and armored than their Greek counterparts. The paintings below provide a more accurate reconstruction of the uniforms, weapons and armor of the Achaemenid troops.

Achemenid Persian officers as they would have appeared during Xerxes’ invasion of Greece.

These were reconstructed by historians, researchers as well as professional army officers in 1971. Suffice it so say, that the movie portrayal and historical veracity are widely divergent. Note the colors on the uniforms as well as the equipment (and virtually no armor). But at least the creators of the 300 picture admit that they are basing their “Persians” on cartoon-like demon characters.

The Size of Xerxes’ Invasion Force.

Few question the fact that Xerxes’ army was huge and that the Greeks were outnumbered. The question is “by how much”? The trailer of the movie states:

“They [the Spartans] were 300 men against a Million”.

The main source of these accounts for modern European scholarship is Herodotus, who actually cites 1,700,000 invaders (Herodotus, VII, 60). Herodotus, who wrote after the Greco-Persian wars of Darius and Xerxes had ended, and before the age of Alexander.

Herodotus (484-425 BC)

Herodotus lists a total of 46 nations mustered by Xerxes in his invasion of Greece (see Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapter 5). The vast numbers of troops were actually a liability as co-ordination and communication and logistical support must have been complex, particularly in contrast to the much smaller and compact, and linguistically uniform, Greek force.

Nevertheless, it is unfair to pin these quantitative citations solely on Herodotus. The Greek tragedy by Aeschylos, The Persians, describes the Greeks facing Xerxes’ armies as facing "a great flood of humans…a wave of the sea that cannot be contained by the most solid dikes (The Persians, lines 87-90)…” and ”…a rash ruler of populous Asia [Xerxes] pushes a human herd to the conquest of the entire world" (The Persians, 73-75).

It was from the mid-19th to the early 20th centuries when a number of European scholars began to question the fantastic numbers cited by Herodotus. European researchers such as Gobineau and Delbrueck began to seriously doubt the numerical claims made by Classical sources. The table below cites some of the researchers of the period who provided the following estimates as to the actual size of Xerxes’ invading armies:

|

Scholar |

Citation and Year |

Estimated number of Xerxes’ Troops |

|

Eduard Meyer |

As cited in William Kelly Prentice, “Thermopylae and Artemisium”, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 51, 1920 p. 5-18 |

100,000 plus an equal number of non-combat support personnel |

|

Ernst Obst |

Der Feldzug des Xerxes in Klio, Beiheft 12, Leipzig, 1914, p. 88 |

90,000 |

|

Comte de Gobineau |

Histoire des Perses [History of the Persians], Volume II, 1869 p. 191 |

90,000 |

|

Reginald Walter Macan |

Herodotus, The Seventh, Eighth and Ninth Books, London, 1908, Vol. II, p. 164 |

90,000 |

|

William Woodthorpe Tarn |

"The Fleet of Xerxes", The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 28, 1908, p. 208 |

60,000 |

|

Hans Delbrueck |

Die Perserkriege und die Burgunderkriege, Berlin, 1887, p. 164 |

55,000 |

|

Robert von Fischer |

"Das Zahlenproblem in Perserkriege 480-479" Klio, N. F., vol. VII, p. 289 |

40,000 |

Most modern scholarship appears to accept the figure of 100,000-200,000 invading troops, a figure consistent with the population base of the Achaemenid Persian Empire at the time (Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapter 5). Even if the Persian Empire had had the population base to produce 1,700,000 troops, it would have faced a gargantuan task in organizing and deploying these without the benefit of modern computers and communications technology. Even if such an army could be organized to set off on the mammoth journey from Asia to Greece, ancient logistics and supply would not have been able to sustain such fantastic numbers of troops in so ambitious a campaign. These capabilities date from far more recent modern times, from the time of the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the advent of the railway and telegraph.

At Thermopylae, the Greek numbers were close to 6000, when counting all of the Spartans and Greek kinsmen. Still, even if we take the lowest estimate of 40,000 Achaemenid Persian troops, the Greeks would have been vastly outnumbered, especially during King Leonidas’ last stand.

Few have addressed the engineering feats that Xerxes’ engineers accomplished in building the world’s first true bridge between Asia and Europe. For an introduction of the Engineering feats that led to the invasion of Europe from Asia Minor (modern Turkey), you may wish to consult the History Channel program:

“Engineering an Empire: The Persians”

http://store.aetv.com/html/product/index.jhtml?id=77071

The show is also available in 5 parts on youtube – part 4 narrates the engineering aspect of Xerxes’ invasion of Greece:

Part 1:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eKN-gZuSH2o&mode=related&search=

Part 2:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pdqmdB_Sbtc&mode=related&search=

Part 3:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bykHGRD_BZ4&mode=related&search=

Part 4:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WNWmaMTTesI&mode=related&search=

Part 5:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFPoe06ThRU&mode=related&search=

A Final Note: The Battle of Salamis.

There are other inaccuracies in the movie as well, especially with regards to the Greek perspective. First, the Spartans were not exactly “democratic” in the Athenian sense; theirs was a hierarchical and militaristic society. To argue that the Spartans were “fighting for Democracy” is somewhat simplistic. It is correct however that the Spartans fought for the glory of Greece, which included Democracy. That does not necessarily mean that the Spartans specifically stood for Democracy as the Athenians and Ionians did.

Second, the 300 Spartans were not alone in their last stand – they were accompanied to the death by at least 300 Thessapian Hoplites, who fought shoulder to shoulder beside them. The fact is that Xerxes finally won at Thermopylae and pushed through into Greece. The Battle that actually saved Greece from total conquest occurred at sea: the Battle of Salamis, after the forcing of Thermopylae. Xerxes could not maintain or expand his European land conquests if he could not control the seas. The Greeks under the bold leadership of Admiral Themistocles lured Xerxes’ fleet into a trap in the straits between Salamis itself and Piraeus.

Typical of the drama of Greek politics, Themistocles, the man who had rescued Greece from the jaws of defeat, was later condemned as a traitor to Greece and forced to flee Athens! Even more ironic is the fact that Themistocles was given shelter by Artaxerxes I, the successor of Xerxes I! In my opinion, it would be fascinating to have a historically balanced movie that would portray the lives of Themistocles, Xerxes, Artemesia, and Artaxerxes.

(4) The Error of Xerxes: the Burning of Athens

The greatest blunder committed by Xerxes in his invasion of Greece were his very un-Persian actions in ordering the city of Athens to be torched, including the Acropolis.

The Acropolis in Athens

Xerxes’ troops destroyed many towns, villages, farms and temples. These actions stiffened the Greek determination to resist and expel the invader from their soil. As I have previously noted, the statues of sacred Greek gods were confiscated and brought to Persia – an action that only fueled the intensity of the Greek desire to seek vengeance. This culminated in the invasion and conquest of Persia by Alexander the Great in the 330s BC.

Xerxes soon realized the error of his actions, but it was too late. His offers to rebuild Athens after the battles were firmly rejected by the Greeks. Most significant however was the fact that Xerxes had broken the tradition of tolerance and respect that had been shown by Cyrus the Great towards captured cities. How would history have been different had Xerxes behaved in Athens as Cyrus had in Babylon? One thing is certain: the West has never forgiven Xerxes’ invasion of Classical Greece.

(5) The “West” battling against the “Mysticism” of “the East”

Towards the end of the movie, there is a statement to the effect that the war is against “the Mysticism and Tyranny” of Persia. How does one wage war on “Mysticism”? As a student of history for 20 years, I honestly was not aware that Xerxes’ invasion was about bringing (or forcing) “Mysticism” upon Europe, at least in the historical sense. The directors and producers of the 300 movie do not appear to have given much thought to the consequences of this proverbial Hollywood “one-liner”, however it does contain a powerful latent message: “the East” stands for “Mysticism”. In that case, what does “the West” stand for? I would surmise the antithesis of Mysticism – namely, Reason and Learning”.

Few would question the fact that the Greeks pioneered much of what we cherish today with respect to logic and philosophy: Greeks (like all great peoples of history) are integral to world civilization. But any type of assumption that ALL of learning has been historically confined to Greece is very much a recent interpretation (from the late 17th century) – and if I may be so bold, it is also an “Orientalist” viewpoint.

While outside the scope of this discussion, it may surprise some readers to know that a number of the greatest Greek minds of the Classical era, Pythagoras, Plato, Thales, and Democritus, traveled to the Persian Empire to take advantage of the centers in learning in Persis, Babylon and Egypt, notably in the fields of astronomy, mathematics, physical sciences, geometry and theosophy (see Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapter 4).

|

Pythagoras (582 - 500 BC) |

Plato (4th century BC) |

|

Thales (624-546 BC) |

Democritus (460 – 370 BC) |

The Greeks, like many other of the learned and civilized peoples of antiquity, also had their share of superstitions as well. Very few are aware that the study of Astronomy was actually prohibited in ancient Athens in the 5th Century BC; any such studies were labeled as blasphemy. Anaxagoras of Clazomenae (Ionia, modern Western Turkey) was actually expelled from Athens because of the hypotheses he proposed about the sun. The Achaemenid Persians certainly had their superstitions. One vivid example is that of Xerxes “punishing” the Aegean Sea by having the waves lashed – the king was angry that the sea had been so turbulent during his invasion of Greece.

The evolution of learning very much resembles the evolution of human rights in history: it is organic and is ultimately achieved by the synthesis and sharing of ideas between nations, cultures and peoples, whether they are engaged in trade, cultural relations or war.

For further references consult the reference list of discussion item (1).

(6) The Portrayal of Iranians and Greeks

What struck me most vividly in this movie was the following question:

Where are the Greek actors in this movie? After all, is this movie not narrating a story about ancient Greece?

The straight forward answer would be that the movie producers were depicting the characters of a graphic novel, which may explain their casting decisions. There still remains the question however of why not at least consider utilizing Greek actors to portray Greek historical characters?

Hollywood’s is intent on conveying a certain “image” of the Classics. Perhaps there is a desire to “Nordify” ancient Greece just as there is a desire to “Orientalize” the ancient Iranians. At least the portrait of King Leonidas in the movie was consistent with the depictions of ancient Greeks as seen in the vases of Classical Greece. For a previous discussion of the depiction of Greeks and Iranians in Hollywood by the author, kindly consult:

The Alexander Movie: How are Greeks and Iranians Portrayed?

http://www.ghandchi.com/iranscope/Anthology/KavehFarrokh/farrokh6.htm

When it comes to the portrayal of the Iranians and the Greeks, I find the following observation by Dr. Ahmad Sadri (College Professor of Islamic World Studies, Lake Forest College) rather astute:

“Snyder’s Persians – I am not talking about the disposable extras covered up to their eyes in male burqas – are predominantly black and by implication of mannerism and affect, homosexual. Allowing the widest berth for the genre and medium one still marvels at Snyder’s audacity in demonizing the “Asiatic hordes” while morphing the Spartan warrior into the typical white American survivalist. Snyder’s Spartans are white guys fighting a sea of racially inferior blacks, yellows and browns. ”

As I walked out of the theater during the closing credits, I heard the following comment by one of the viewers in the audience:

“This movie chose really excellent Eye-ranian [Iranian] actors – they showed them so accurately – just what you would expect them to be…”

It is very interesting that in this movie (and its comic book original) insists on portraying the “Persians” (especially the elites) as black Africans. In the movie trailer, King Leonidas is shown kicking the “Persian messenger” into a bottomless pit and shouting “This is Sparta!”:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bCwT0TF6fa4

Movie Trailer for 300

The “Persian messenger” is black. Other Persians in the film are also black, including a “Persian” general executed by Xerxes and a “Persian” emissary sent to communicate with Leonidas – the latter role being played by talented actor Tyrone Benskin (Marked Man, 1996; Sci-Fighters, 1996, etc.):

Tyrone Benskin

Interestingly, the recent movie, Alexander (starring Colin Farrell), featured (with few exceptions) Arabic speaking North Africans instead of Iranians in the role of “the Persians”, whereas the 300 book and movie portrays Iranians as Africans. As we shall see later below, there are indications that Hollywood (in general) believes that such portrayals, however inaccurate, “sell better” in North America and Northwest Europe.

There are NO Greek or Roman references to black “Persians” and Greco-Roman sources also CLEARLY distinguish between the Arabs of antiquity and “the Persians.” Greek vase art from the Classical period show “the Persians” as remarkably similar to the Greeks – their differences are in wardrobe and equipment:

In this discussion, I will make use of the term “Iranian” as opposed to “Persian” as the former is more inclusive and includes Kurds, Azeris, Persians and other peoples of Iranic origin. The term “Persian” was used by the Greeks to designate all Iranian peoples of the time, when in fact, the Medes and the Scythians (Saka) were also partners in empire alongside the Persians.

There is a dearth of primary sources to help archeologists, anthropologists and historians reconstruct the ancient Iranians contemporary to Xerxes’ invasion of Greece. Note the clear distinction that is made between African (Ethiopian) and Caucasian (Iranian) troops by Greek vase-arts:

[

[

African levy in Achaemenid service (left) and Iranian troops (right) as portrayed in Greek art. The Greeks clearly distinguished between the Iranians (portrayed as Caucasians) and Africans in their artistic works (Nick Sekunda, The Persian Army, Osprey Publishing, 1992, p.16-17).

As a Classical historian, Sekunda has reconstructed King Xerxes, Iranian warriors as well as their African contingents:

Ethiopian marine (left), Iranian warrior (centre) and Iranian spearbearer (Nick Sekunda, The Persian Army, Osprey Publications, 1992, Plate C; Paintings by Simon Chew). Note how these re-constructions differ from how Iranians have been portrayed in the “Alexander” and “300” movies.

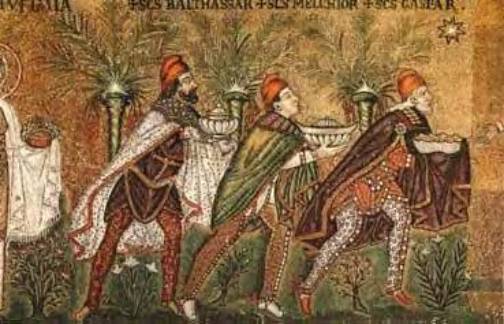

The Iranians shown in the centre and right would not look unusual in today’s Iran. Later Roman sources also provide a very clear and detailed pictorial view of the Iranians contemporary to the 3rd – 7th centuries AD. Note the Roman drawing of the three Iranians in Persian dress from Ravenna, Italy:

Roman depiction of Iranian nobles depicted here as the three wise men. It is clear that the Romans were objective in their portrayal of their enemies, the Parthians and the Sassanians.

The cultural and linguistic legacy of the Indo-European or “Aryan” arrivals on the Iranian plateau since at least the 2nd millennium BC continues to resonate in modern Iran, and in Iranian speaking Kurds in the Near East as well as the Caucasus and Central Asia. Please note that I use the word “Aryan” with considerable caution here, as we are referring to the Old Iranian from “Airya” and/or “Eire” which loosely means “Lord” or “freeman” – the closest European equivalent is the Irish word “Eire”.

However what makes Iran unique on the world stage of history is the fact that Iran is the world’s oldest multi-ethnic and multi-language nation in history. Before the Indo-European arrivals, Iran was already host to a vibrant Elamite civilization to the southwest as well as Manneans and Hurrians to the northwest and west. These peoples fused their culture with the incoming Iranian speaking Indo-Europeans – Iran has been a evolving tapestry of peoples ever since. In any of Iran’s cities one can find an array of faces and languages – from Turkish in the northwest to Arabic in south. There are Iranians of African descent as well, these being partly descended from Ethiopians who were settled along Iran’s Persian Gulf coast during the Achaemenid era.

Genetic researchers have conducted a number of detailed genetic studies on Iran, the Caucasus as well as the Near East. One example is a recent study by Professor Martin Richards and 26 other researchers who conducted a thorough genetic analysis of Turks, Arabs, and Iranians. The latter focused mainly on Iranian-speaking Kurds (mainly descendants of the Medes) and the mainly Turkish speaking Azerbaijanis of Iran (themselves descendants of the Media Atropatene – one of the ancient homes of the aforementioned Zoroastrian religion). There was also a large sample of Ossetians in the study; Ossetians speak variations of the Old Iranian Avestan language (the basis of many of the old Zoroastrian hymns). Armenians were also studied.

Put simply, the results show a very high incidence of U5 lineages – genes common among modern Europeans as a whole. The results are aptly summarized as such:

“…many Armenian and Azeri types are derived from European and northern Caucasian types (p.1263)…The U5 cluster… in Europe… although rare elsewhere in the Near east, are especially concentrated in the Kurds, Armenians and Azeris…a hint of partial European ancestry for these populations – not entirely unexpected on historical and linguistic grounds (p.1264)”

[Richards et al., (2000). Tracing European founder lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA pool. American Journal of Human Genetics, 67, p.1263-1264, 2000]

There were no genetic links between the Iranian groups cited and the Arabs of that study. Interestingly, a number of Turks from western Turkey in the Richard study showed incidences of the European gene markers, indicating mixtures with Greek and other European populations in the course of Turkish history. Suffice it so say that Caucasians with so-called “European” appearances are nothing unusual in today’s Iran – they are part and parcel of today’s multi-ethnic Iran.

Photograph taken in 1971 by Ali Massoudi of a girl from Rasht in Gilan province, Northern Iran (Source: R. Tarverdi (Editor) & A. Massoudi (Art editor), The land of Kings, Tehran: Rahnama Publications, 1971, p.116).

There seems to be very little international motivation to understand the multifaceted nature of the Iranians themselves as well as their history and culture. A survey by Jack Shaheen (author of “The TV Arab”, 1984) in the early 1980s found that over 80 percent of North Americans wrongly believe Iranians to be Arabs and to speak Arabic. This may explain in part the persistence of the “Hollywood Persian” image in the entertainment industry.

Addendum: Is there a Case of Institutionalized Discrimination against Iranians in Hollywood?

There are disturbing indications that a subtle form of racism has at times been applied in Hollywood against actors and extras of Iranian origin. A vivid example of this was demonstrated over 15 years ago during the filming of the action movie “The Hitman”, starring Chuck Norris, released in 1991.

A portion of the filming took place in North Vancouver, British Columbia in Canada in 1989-1990. The directors and Norris put ads in the local papers asking for Iranians to audition as extras for the movie. What happened next is as comical as it is tragic.

Many of the “Iranians” who showed up on the set proved to be a major disappointment to Norris. This is because, far from fitting into the popularized “Hollywood Persian” stereotype, the potential Iranian extras displayed a variety of phenotypes. The group included Iranians from the northern regions (Gilan, Mazandaran, Semnan, Talesh), the northwest (Azerbaijan) and the west (Lurs and Kurds) as well people from Isfahan and Tehran. Many of these could appear as “regular Americans” on the street or in your local shopping mall. The directors and Norris were very disappointed at this and were visibly upset. Here is an excerpt by one of the auditioning Iranian extras on the set (his identity withheld at his request):

“…the directors came to the set and were upset to see us. Among us were Mashadis of Turcomen background [with Central Asian/Far eastern appearance], Baluchis and more blondish types from the north and west…Norris and the directors said ‘what are these Caucasians doing on the set? I said I want ‘Iranian extras’ not Caucasians…Americans like to see real Iranians…”

The recruiters then explained that the “Caucasian” extras were natives of Iran from the north, Tehran and the northwest, but to no avail. Norris and the directors insisted on expelling the (so-called) “Caucasians” from the set. Similar reports have been reported by the aforementioned Jack Saheen with respect to Arab actors of Lebanese origin. Hollywood certainly is not free of human bias, seriously compromising any educational value of some of its “historical” releases. This leads us to the fantastic depiction of Xerxes himself:

If the portrayal “the Persians” is fictional, that of Xerxes has set new parameters for creativity. For a thorough analysis of the actual appearance of Xerxes, kindly consult Daniel Pourkesali’s article:

Movie 300: A Tale of Pure Fantasy

http://www.payvand.com/news/07/mar/1157.html

As noted astutely by Daniel Pourkesali, the movie’s portrayal of Xerxes is based faithfully on the graphic novel, but widely divergent with historical depictions of Xerxes. Below is his portrait as he appears in Persepolis:

An Iranian portrait of Xerxes

Below is another reconstruction by Professor Sekunda of Xerxes as he would have appeared in Greece.

Court Eunuch (left), King Xerxes (centre) and Royal Spearbearer (right) (Nick Sekunda, The Persian Army, Osprey Publications, 1992, Plate B; Paintings by Simon Chew).

Below is a Classical Greek depiction of Xerxes when he was still a prince in the court of his father, Darius the Great:

Greek depiction of Darius the Great (seated on throne in top row at centre) debating with his advisors as to whether he should invade Greece in 490 BC. Prince Xerxes is seen on the top row, second from the right.

The Miller/Warner Brothers portrayal of Xerxes and the way he would have historically appeared are literally as different as day and night. Professor Ephraim Lytle, a Hellenistic historian at the University of Toronto in Canada, has aptly summarized the picture’s portrayal of Xerxes and “the Persians”:

“300's Persians are ahistorical monsters and freaks. Xerxes is eight feet tall, clad chiefly in body piercings and garishly made up, but not disfigured. No need – it is strongly implied Xerxes is homosexual which, in the moral universe of 300, qualifies him for special freakhood.”

[Professor Ephraim Lytle, “Sparta? No. This is Madness”, The Toronto Sun, March 11, 2007]

(7) A Note on the Iranian Women in Antiquity

I received the following e-mail from “Pedram” which aptly summarizes this segment of our discussion: "Have you seen the movie? I have heard that it was so insulting to Persian women… "

The 300 movie certainly portrayed Iranian women as shallow, mindless “harem girl-objects”. This is even testified to in the trailer:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bCwT0TF6fa4

The portrayal of Iranian women in this movie is not only grossly inaccurate in historical terms, but also degrading, insulting to women in general. Again, this seems to be derived from a massive sense of ignorance regarding the role of Iranian women in history.

The women of ancient Iran were priestesses (i.e. Temple of Anahita), warriors, leaders and guardians of learning. While a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this article, a few highlights will hopefully serve to arouse the interest of the readers.

Roman sources are very clear in referring to women among the ranks of the Iranian cavalry in the Sassanian era: “in the Persian army…there are said to have been found women also, dressed and armed like men…” [Zonaras (XII, 23, 595, 7-596, 9) in reference to forces of Shapur I]

King

Shapur receives the surrender of Emperor Valerian at

Barbalissos. Female Iranian cavalry officer (left), nobleman of

the Suren clan (with tall “beaked” hat), Emperor Valerian

(kneeling), Roman Senator (man with toga) and King Shapur I

(right) (Farrokh, Elite Sassanian Cavalry, 2005,

Plate A; Paintings by Angus McBride).

King

Shapur receives the surrender of Emperor Valerian at

Barbalissos. Female Iranian cavalry officer (left), nobleman of

the Suren clan (with tall “beaked” hat), Emperor Valerian

(kneeling), Roman Senator (man with toga) and King Shapur I

(right) (Farrokh, Elite Sassanian Cavalry, 2005,

Plate A; Paintings by Angus McBride).

Iranian women organized resistance against the Arabian invaders of the Ummayad and later Abbassid caliphates after the fall of Sassanian Iran (or Persia) in the 7th century AD. Key figures include Apranik, the daughter of General Piran, as well as Azadeh, guerilla resistance leader of Gilan-Mazandaran in northern Iran, and Banu, the wife of the anti-Abassid rebel Babak Khurramdin who led a decades long anti-Caliphate movement from Iranian Azerbaijan (see Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert, 2007, Chapters 4-5).

Iranian women continued to play leadership roles well after the fall of Sassanian Iran (or Persia) to the Islamic invaders of Arabia in the 7th century AD. One example is the governess of Rayy, birthplace of the medical savant Rhazes (near modern Tehran):

Governess of Rayy (Farrokh, Elite Sassanian cavalry, 2005, p.60)

The equality of women with men in enshrined in the Zoroastrian religion itself. One the Zoroastrian fables refers to a conversation between Zoroaster and his daughter Freyne highlighting the fact that it is up to women to choose their mates for courtship and marriage.

(8) “Good” versus “Evil”

A short and final point has to do with the portrayal of “the Persians” as “evil”. In one of the earlier scenes, King Leonidas holds a dying boy who, in reference to the invading host, states softly that the Persians “…came from the blackness…”. It is very clear that “the Persians” are literally portrayed as “evil”.

The retort to this is that the movie is only faithfully reproducing the characters of a harmless comic book. But is it?

How would members of other ethnic communities worldwide feel if their ancestors were being portrayed as monsters, troglodytes, degenerates, and demons? These same producers would probably think twice if they were to portray other nationalities in the manner that they have done with the “Persians”. If my logic (flawed as it may be) is not mistaken, portraying Iranians as monsters, troglodytes, degenerates, and demons is “artistic entertainment”, but other nationalities are exempt from this “art form” as this would be “tasteless and politically incorrect” and would be regarded as a “hate crime”.

The targeting of specific ethnic groups with negative attributes in the name of entertainment dollars is dangerously misinformed and irresponsible. As noted earlier in this commentary, viewers and media outlets (especially in the English-speaking world) are already interpreting much of the movie in a “historical” light. The Greco-Persian wars evoke very intense emotions in northwest European culture, in some ways even more so than in modern-day Greece and Italy. The movie 300 has successfully capitalized on those very emotions in the quest for profit.

It is at this juncture of the discussion, where we must remind ourselves of one of Zoroaster’s chief teachings: Zoroaster taught that good and evil resides in all members of humanity, regardless of racial origin, ethnic membership or religious affiliation. Each person is given the choice between good and evil – it is up to us to choose between them.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Having discussed the issues at length, it is hoped that the reader will appreciate the multifaceted and organic nature of human history. Nations, peoples and cultures have had a symbiotic relationship with one another through trade, cultural exchanges and war. It is these very processes that have shaped our identities and who we perceive ourselves to be today. As the size of our world diminishes daily due to the breathtaking leaps in technology and communications, it is all the more important to make the endeavor to understand history, not in terms of “east” versus “west”, but with the appreciation of human civilization being a collective.

Regards

Kaveh Farrokh

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Dr. Kaveh Farrokh is the author of “Sassanian Cavalry” (Osprey Publishing, 2005). He has lectured at the University of British Columbia as well as Stanford University and has appeared on the History Channel as an expert on ancient Iran. Dr. Farrokh is currently a member of the Iran Linguistics Society, the Persian Gulf preservation Society as well as the WAIS (World Association of International Studies) at Stanford University. His new book, “Shadows in the Desert: Persia at War” by Osprey Publishing is to be released in late April 2007. Available to order here:

http://www.ospreypublishing.com/title_detail.php/title=T1087

Bibliography

Notions of Democracy and Human Rights/What Really Led to War

Abbott, J. (1902). Cyrus the Great. New York and London: Harper & Brothers

Boyce, M. (1987). Zoroastrianism: A shadowy but Powerful Presence in the Judaeo-Christian World. London: Dr. Williams’s Trust.

Curtis, J. (2000). Ancient Persia. London: British Museum.

Delebeque, E., & Bizos, M. (1971-1978). Cyropédie. Texte établi et traduit par Marcel Bizos. Paris : Les Belles Lettres.

Farrokh, K. (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Persia at War. London: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Frye, R.N. (1962). The Heritage of Persia. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Frye, R.N. (1984). History of Ancient Iran. Munich: C.H. Beck.

Moorey, P.R.S. (1975). Ancient Iran. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum.

Oxtoby, W.G. (1973). Ancient Iran and Zoroastrianism in Festschriften : An Index. Waterloo, Ontario: Council on the Study of Religion, Executive Office, Waterloo Lutheran University; Shiraz, Iran: Asia Institute of Pahlavi University.

Spatari. N. (2003).Calabria, L'enigma Delle Arti Asittite: Nella Calabria Ultramediterranea. Italy: MUSABA.

Wiesehofer, J. (1996). Ancient Persia: from 550 BC to 650 AD. London and New York: IB Tauris.

The Greco-Persian Wars and the Battle of Salamis

Cartledge, P. (2004). The Spartans. Random House

Cook, J.M. (1962). The Greeks in Ionia and the East. London: Thames & Hudson.

Farrokh, K. (2005). Elite Sassanian Cavalry. London: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Farrokh, K. (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Persia at War. London: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Head, D. (1992). The Achaemenid Persian Army. Stockport: Montvert Publications.

Holland, T. (2006). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. Doubleday Publishing.

Khorasani, M.M. (2006).Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to end of the Qajar Period. Legat Verlag.

Sekunda, N. (1992). The Persian Army. London: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Wallinga, H.T. (2005). Xerxes' Greek Adventure: The Naval Perspective. Leiden Brill Academic Publishers.

The Portrayal of Iranians and Greeks

Ewen, S. & Ewen, E. (2006). Typecasting: On the Arts and Sciences of Human Inequality. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Parenti, M. (1992). Make-Believe Media: The Politics of Entertainment. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Shaheen, J. (1984). The TV Arab. Bowling green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press.

McChesney, R.W. (1997). Corporate Media and the Threat to Democracy. New York: Seven Stories Press.

See also on-line posting by Darius Kadivar:

Sword and Sandals: Films about Ancient Persia

http://www.iranian.com/DariusKadivar/2003/January/Bigger/index.html

Iranian Women

Interested readers may consult the following sources for further reading:

Brosius, M. (1998). Women in Ancient Persia: 559-333 BC. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Davis-Kimball, J. (2002). Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines. Clayton, Victoria: Warner Books.

Farrokh, K. (2005). Elite Sassanian Cavalry. London: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Farrokh, K. (2007). Shadows in the Desert: Persia at War. London: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Winchester, B.P.P. (1930). The heroines of ancient Persia: Stories Retold from the Shahnama of Firdausi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

| بازگشت به صفحه اول |

]

]